Running Operations Like Zara: A Practical Roadmap for Pakistani Fashion Retailers

1. Why everyone says “We want to be Zara”

In almost every fashion retail strategy discussion, one sentence shows up:

“We want to run operations like Zara.”

When you ask, “What exactly do you mean by ‘like Zara’?”, the answers are usually generic:

- “Fast fashion.”

- “New designs every week.”

- “Nice stores and a strong brand.”

What is almost never discussed is how the engine underneath actually works:

- How Zara structures its supply chain and calendar.

- What it centralises and what it leaves to store teams.

- How it uses data and feedback from stores.

- Which disciplines it enforces that most retailers avoid because they feel uncomfortable.

This article translates Zara’s model into concrete operating disciplines and asks a simple, practical question:

“What is a realistic, de‑risked version of this model for a Pakistani fashion retailer over the next 12–18 months?”

The goal is not to copy Zara blindly. The goal is to move away from a seasonal wholesaler mindset and towards a learning, responsive retail system.

2. What Zara’s economics look like (based on case‑study data)

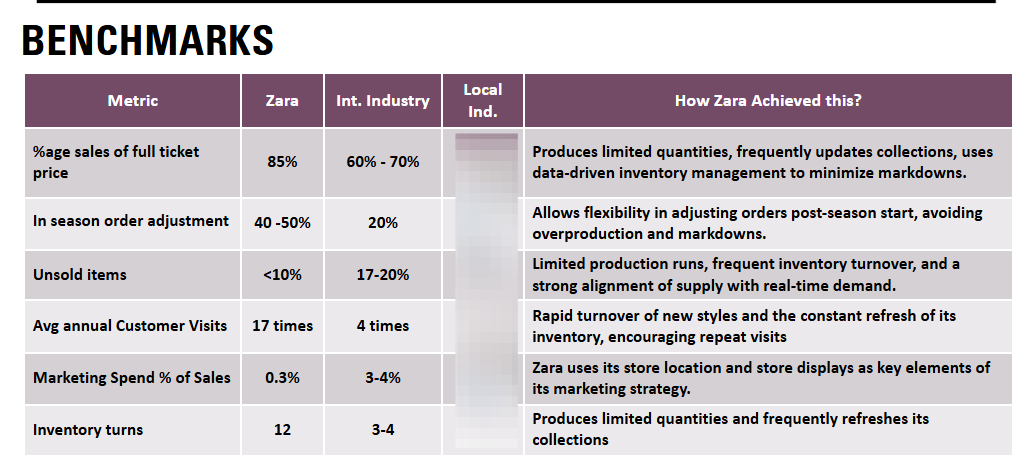

Across multiple case studies and analyses of Zara over the last two decades, a consistent picture emerges:

- Full‑price sell‑through around 85%

Many traditional fashion retailers sell only 60–70% of volume at full price and depend heavily on markdowns. - Unsold stock typically under 10%

Industry case studies often cite 17–20% unsold as normal for conventional players. - Inventory turns around 10–12 times per year

Typical fashion chains operate at 3–4 turns. Many regional players run at 2–3 turns in practice. - Customers in core markets visiting ~17 times a year

Competitors in the same markets see 3–4 visits per year. - Advertising spend around 0.3% of sales

Conventional competitors often spend 3–4% of sales on marketing.

These figures come from different time periods and geographies, so they should be treated as orders of magnitude, not exact targets. But they point to something important:

Zara’s advantage is not only its designs. It is the way it moves stock, learns from demand, and avoids becoming a clearance business.

For Pakistani Fashion CEOs, the key question is:

“Which operating behaviours produce these outcomes – and which of them can I realistically adopt in our context?”

3. Discipline 1 – Treat your best stores as your main marketing channel

Most Pakistani brands think in this sequence:

Product → Campaign → Discount → Store

Zara’s sequence looks more like this:

Location + Store experience → Product rhythm → Very low advertising

Practical elements behind this:

- Prime locations as media spend

Zara spends heavily on locations that guarantee natural footfall and visibility. This spend partially replaces traditional above‑the‑line advertising. - Windows as billboards

Windows are updated frequently (often every 1–2 weeks). The visual message is simple: “This is what’s new this week.” Customers are trained to expect constant change. - Staff as live mannequins

Store staff wear current collection looks, tuned to local cultural norms. The store feels like a moving lookbook instead of a static rack of merchandise.

What a Pakistani retailer can do in 3–6 months

You do not need an Inditex‑level budget to adopt the logic:

- Choose your top 10–15 stores and treat them as media assets.

These are the stores where you invest in windows, mannequins, and staff styling first. - Create a simple VM calendar: one clear window concept every 2 weeks for those stores.

- Define a weekly “look of the week” that staff wear using your own merchandise.

- Reallocate a small percentage of digital/ATL spend into:

- Better window execution.

- In‑store lighting and fixtures.

- Training for staff styling.

This is the first mindset shift: see the store as your main advertisement and your marketing budget as support to that, not the other way around.

4. Discipline 2 – More styles, fewer units, and planned scarcity

Zara does not win because it perfectly predicts trends. It wins because it places many small, fast bets and learns quickly.

Key practices documented in case studies:

- Designing tens of thousands of styles per year, but producing each in relatively small quantities.

- Many fashion items are designed, produced, and reach the shop floor within 10–15 days for European markets.

- A large portion of the assortment lives on the shop floor for only 3–5 weeks before being retired, repeated, or replaced.

- Stock‑outs on successful items are not treated as disasters; they are part of the operating logic that creates urgency.

The result:

- Customers visit more frequently because “there is always something new.”

- Full‑price sell‑through improves because less volume is committed upfront per style.

- Clearance becomes a safety valve, not the main profit model.

Contrast with a typical Pakistani fashion chain

- Large quantities per design, decided months in advance.

- Very long style life on the shop floor (often a full season, sometimes 6+ months).

- Habitual reliance on end‑of‑season sales to clear mistakes.

A realistic starting point

You cannot flip your entire buying model in one season. But you can:

- Pick one or two key lines (e.g. ladies’ casual shoes, pret kurtas).

- For these lines:

- Reduce quantity per design by 20–30% versus your normal buy.

- Increase the number of designs by 10–20%.

- Commit to a 3–4 week review: for each style, decide to back, repeat, or kill based on sell‑through and feedback.

- Track this pilot separately on:

- Full‑price sell‑through.

- Discount depth at clearance.

- Gross margin and sell‑through speed.

If reporting is weak today, start manually: an Excel or simple BI view tracking 20–30 pilot SKUs in 10–20 stores on units sold, stock, and size‑curve health. Get the discipline right before automating.

What this means for merchandisers and sourcing

For this pilot to work, KPIs and expectations must change:

- Merchandising must know that for the pilot capsule, success equals better full‑price sell‑through and turns, even if there are some stock‑outs. Leadership should explicitly state that merch will not be punished for every stock‑out in pilot stores.

- Sourcing and buying may need to accept slightly higher unit cost on pilot styles in exchange for lower leftover stock and markdowns. For example:

- Use more flexible vendors for pilot capsules.

- Lock core fabrics upfront and run multiple styles on the same base to meet MOQs.

- Use local or near‑shore vendors for fast fashion lines, and keep long‑lead offshore vendors for basics.

- When considering transfers to fix broken size runs, apply a simple rule: only transfer if expected full‑price sales gain clearly outweighs logistics cost and effort. Transfers should be targeted, not random.

5. Discipline 3 – A strict, visible supply‑chain rhythm

Zara’s supply chain is famous for being fast, but just as important is that it is predictable and rhythmic.

Core elements from published cases:

- Stores place orders twice a week on fixed days.

- Orders are processed centrally and shipped on a fixed timetable, like a bus schedule.

- European stores typically receive shipments within 24–36 hours of dispatch; more distant markets within about 48 hours.

- Product arrives at stores pre‑priced, labeled, and often pre‑hung, ready to go straight to the floor.

This rhythm means everyone knows:

- When stores must place orders.

- When DCs must dispatch.

- When stores will receive stock.

The system can deliver constant newness without permanent firefighting.