The 3.7% Growth Lever Hiding in Your Store Timetable

During a store visit, the AI Transformation team saw a familiar scene.

It was early afternoon. Staff were deep in inward tasks—stock counting, GRNs, cleaning. Lunch breaks overlapped. A mother with two children walked in, looked around, waited, tried to get attention and then quietly walked out. No one was free to serve her. The sales team looked tired and slow.

Yet, when the daily report came out that night, the store showed “normal” performance. Sales were on plan. Nothing in the data proved that the missed opportunity had ever existed.

The question that started the project:

“What if the real growth lever isn’t more stores, but how we use the 12 hours we already have?”

Problem and stakes: averages hiding problems

This project was done for a large fashion and footwear retailer with around 270 stores.

How performance was viewed before:

- All reporting was at day level: daily sales, daily traffic, daily conversion.

- 12-hour shifts with fixed routines were the norm. Staff came in, did everything (inward tasks + customer service) in one long stretch.

- There was no concept of “day-parts” or time-of-day performance.

On store visits, leadership could see the symptoms:

- Some customers not getting attention, especially in certain parts of the day.

- Staff visibly tired in late afternoon, slow to respond.

- Internal tasks and cleaning eating into selling time.

But these issues were invisible in the data, and therefore invisible in discussions at Head Office.

Strategic stakes for fashion executives:

- Find growth without heavy capex (no new stores, no big campaigns).

- Improve conversion and NPS through better service.

- Use existing staff more productively, without burning them out.

The hypothesis:

“Inconsistent service and missed sales opportunities are concentrated at specific times of day. If we see the day by time slot, we’ll find a new growth and efficiency lever.”

What we did

1. Build a time-of-day view

Scope:

- ~270 stores.

- 1 year of data.

- Data sources: footfall (FF) and conversion portal + POS.

We broke the trading day into three time slots that reflected real store life:

- Before 3 pm – morning + early afternoon

- 3–7 pm – after-school and pre-evening peak

- After 7 pm – evening and late shopping

For each store and slot, we calculated:

- Traffic contribution (% of daily footfall)

- Sales contribution (% of daily sales)

- Gap (Sales% – Traffic%) – a simple way to see where we over- or under-performed

- ATV (average transaction value)

- Conversion

This created a store × time-slot lens that had never existed before.

2. What the data revealed

At chain level, the picture was clear:

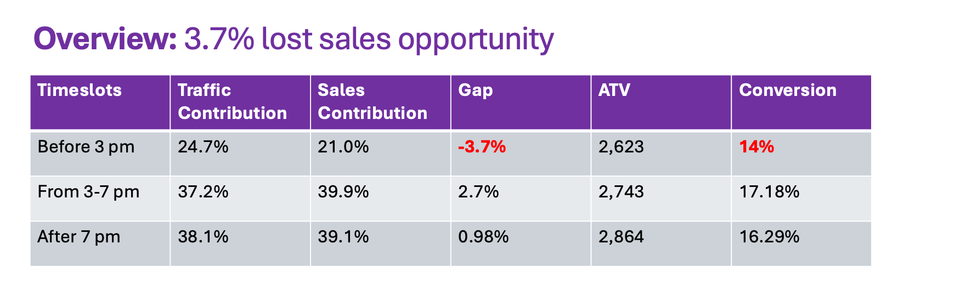

| Timeslot | Traffic % | Sales % | Gap | ATV | Conversion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before 3 pm | 24.7% | 21.0% | −3.7% | 2,623 | 14.0% |

| 3–7 pm | 37.2% | 39.9% | +2.7% | 2,743 | 17.18% |

| After 7 pm | 38.1% | 39.1% | +0.98% | 2,864 | 16.29% |

Key insights:

- Morning slot (Before 3 pm)

- Gets almost a quarter of daily traffic (24.7%) but only 21.0% of sales.

- Gap of −3.7 percentage points: customers are coming, but we are under-selling them.

- Lowest conversion and lowest ATV.

- In many stores with more rural catchments, this slot is the main traffic window—people coming from nearby villages and small towns earlier in the day.

- 3–7 pm and After 7 pm

- These slots carry the bulk of sales, with better conversion and higher ATV.

- Evening (after 7 pm) is particularly strong on ATV—likely driven by families and working professionals shopping after work.

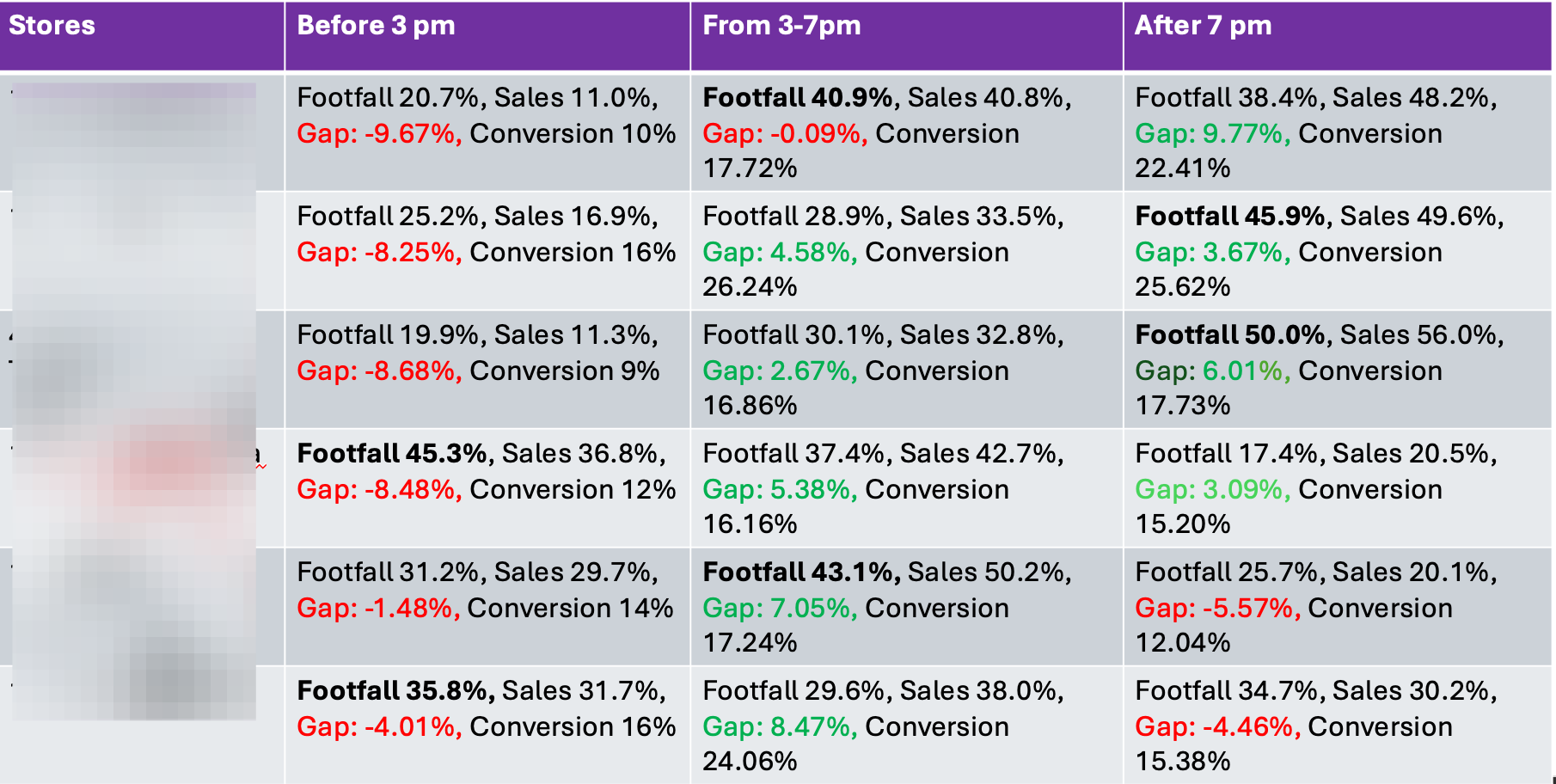

We also saw cluster-level differences:

- Rural or semi-urban stores: heavier traffic earlier in the day.

- Urban, mall, or office-area stores: stronger traffic and sales in evening slots.

- Some stores showed very large negative gaps in the morning (e.g., >8–10 percentage points), while others over-performed in the same slot. These became natural internal benchmarks.

In simple terms:

The business was treating the day as one 12-hour block, but the data showed three different customer missions with different needs and potentials.

Key design decisions and operational changes

1. Rebalancing shifts and workloads

Based on the analysis, the operations team redesigned how the 12 hours were used:

- Rebalanced headcount across time slots

- More staff and energy in higher-potential slots.

- Lighter staffing in genuinely low-traffic windows.

- Moved inward-facing tasks out of selling time

- GRNs, replenishment, stock counts, audits, and training were moved toward low-traffic periods.

- Sales staff were asked to be fully customer-facing in identified high-opportunity windows, especially mornings in rural-catchment stores.

- Changed cleaning routines

- Hired contract cleaners so sales staff spent less time cleaning and more time serving customers.

- Improved lunch and break patterns

- Staggered breaks to avoid “dead zones” on the shop floor.

- Ensured not all strong sellers were off the floor at the same time.

This was not a tech project; it was an operating model change for stores.

2. Time-specific commercial ideas (proposed, not yet executed)

Inspired by telcos (who use time-based offers to fill network slack), the team proposed:

- Targeted morning offers in low-traffic slots:

- For example, discounts or bundles for housewives or morning shoppers.

- Stylist or expert visits in slow periods to attract specific segments.

- Linking VM and range to day-parts (e.g., more family-oriented displays in high family-traffic slots).

These ideas were shared as a roadmap but not yet fully tested, mainly due to limited cross-functional buy-in at the time.

Impact and adoption

Because this was a first-time lens, there was no prior time-of-day baseline to compare against. The impact measurement was therefore more qualitative and directional than perfect.

What was observed:

- Employee satisfaction improved

- Field feedback indicated staff felt shifts were more sensible, peak times were better supported, and expectations clearer.

- Less frustration from doing internal tasks while customers waited.

- Conversion increased slightly

- Where new shift patterns and task movements were followed properly, operations teams saw a small but visible uplift in conversion, especially in problematic morning slots.

- The effect was in the low single digits (assumption, based on directional comments rather than a controlled A/B test).

- Better management conversations

- Store managers and regional heads started to talk about “morning performance” and “evening performance” separately, not just daily averages.

- Problem stores could be diagnosed by time slot, not just format or region.

Ownership:

- Implementation was driven primarily by Store Operations and Sales.

- HR and other functions were involved but did not fully redesign policies or processes yet.

What helped, and what held it back

What helped

- Simple metrics

- Traffic%, Sales%, Gap, ATV, and Conversion by time slot were easy for leadership to understand and act on.

- Clear link to outcomes

- Connecting roster and task decisions to conversion, not just payroll costs, made the discussion commercial, not just HR.

- Internal benchmarks

- Stores that over-performed in “difficult” slots (e.g., strong mornings) were used as internal case studies.

What held it back

- Not including in WBR made adoption slow

- Initiatives that were followed up and reviewed weekly showed strong results, which did not happen in this case

- Without coordinated action, some of the commercial upside remained theoretical.

- No slot-level KPIs

- Targets and incentives remained at daily level, so focus drifted back to averages over time.

- Change in habits is hard

- Stores were used to “we do everything all day.”

- It took time and discipline to build a culture of “we protect selling time and organize tasks around traffic.”

Key lessons:

- Start with store archetypes, not the whole chain

- Define day-part playbooks for 2–3 store types (e.g., urban mall, high-street, rural catchment) instead of applying one pattern to 270 stores.

- Tie rosters to productivity by slot

- Track sales per labor hour by time slot.

- Make roster approval dependent on meeting basic productivity thresholds.

- Embed day-parts into weekly reviews

- If leadership only reviews daily numbers, slot-level focus fades.

- Regional reviews should have 2–3 slot-level charts per key store until the habit sticks.

- Plan a proper impact pilot next time

- Use A/B store groups, define a clear baseline period, and measure time-of-day impact more rigorously.

Playbook: how another fashion retailers can copy this

You can treat this as a 90-day initiative.

Step 1: Check your data plumbing

- Confirm you have timestamped POS data and, ideally, footfall counters.

- If not, start with POS timestamps alone—sales per hour is still useful.

Step 2: Define 3–4 time slots that match your reality

- Use store operations knowledge to define consistent time bands (e.g., opening–3 pm, 3–7 pm, after 7 pm).

- Keep them simple enough that managers can remember.

Step 3: Build a basic report

For each store and slot, show:

- % of daily traffic

- % of daily sales

- Gap (Sales% – Traffic%)

- Conversion and ATV

Highlight:

- Slots with negative gaps and low conversion.

- Stores that consistently under-perform in a given slot.

- Stores that over-perform (your internal “best practice” labs).

Step 4: Run a 90-day pilot in a manageable set (e.g., 20–30 stores)

- Redesign shifts and lunch breaks by slot.

- Move internal tasks into low-traffic periods.

- Add simple slot-level KPIs (e.g., morning conversion target, evening sales per labor hour).

- Track impact weekly.

Step 5: Codify and scale

- For each store archetype, create a simple day-part operating guide:

- Staffing levels by slot.

- Task windows (when GRNs, stock counts, cleaning happen).

- Service expectations (who covers which zone when traffic peaks).

- Once stable, bring in Marketing, VM, and Supply Chain to design time-specific tactics (offers, displays, replenishment focus).

Preconditions

- At least basic hour-level POS data.

- Some flexibility in how you schedule staff (not entirely fixed shifts).

- Operations leadership willing to own and enforce new patterns.

Pitfalls to avoid

- Treating this as a one-off “analysis project” with no operating model change.

- Overcomplicating time slots and KPIs.

- Ignoring cross-functional alignment; without Marketing/VM/Supply Chain, you only capture part of the upside.

Closing: a low-capex lever most retailers ignore

Most fashion retailers talk about growth in terms of new stores, new categories, or price increases.

This project shows there is another lever, already sitting in your data:

Time-of-day performance.

By simply looking at when customers come, who they are by store type, and how staff and tasks are arranged around them, you can unlock a few percentage points of growth and better service—often equivalent to opening several new stores—without spending heavily on capex.

For a CEO or COO, the question to ask your team is simple:

- “Show me conversion and sales by time of day and store type—and then show me how our shifts and routines line up against that.”

The answer to that question might reveal your next, low-cost growth lever.

Member discussion